Direct Response Copywriting: Classic Examples + Tips

Direct response copywriting is a marketing technique where you speak directly to your customers, encouraging them to take action now instead of later. It can take many forms, including writing and managing social media campaigns, email newsletters, press releases, banner ads, landing pages, and video scripts.

Typically, the structure of a direct response copywriting campaign includes a catchy headline, captivating messaging in the main copy, and a prominent call-to-action (CTA) at the end to close out the deal.

A Perfect Example of Direct Response Copywriting

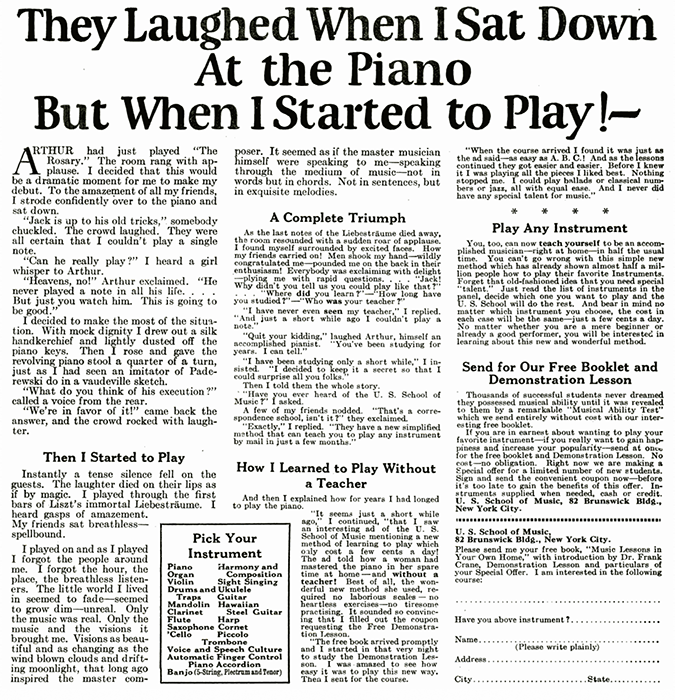

Back in 1927, when print marketing was starting to gain traction at an unprecedented pace, along came John Caples. After participating in a couple of apprenticeships and taking an engineering job, John quickly became bored and decided to try his luck in professional advertising. Soon, he was tasked with creating a mail-order advert for the US School of Music, and what followed laid the foundations for modern-day direct response advertising.

John simultaneously (albeit, inadvertently) used the backbone of the AIDA copywriting framework, advertising copywriter Eugene Schwartz’s concept of speaking to the fears and desires of your audience, and legendary mythologist Joseph Campbell’s storytelling template of the hero’s journey to compose one of the greatest direct response ads of all time.

The ad makes use of an emotionally charged headline to get the reader to pay attention: “They laughed when I sat at the piano—But when I started to play!” Getting the reader’s attention is the first stage of the AIDA framework.

At the same time, Mr. Caples cleverly formats the headline to convey just enough information without spoiling the outcome. Readers who come across this ad will be interested to continue following along with the rest of the story, which is a textbook example of the cliffhanger trope and the second stage of the AIDA formula.

Once the prospect takes the bait, John introduces the ad’s protagonist—Jack. In this scenario, Jack is a substitute for the target audience’s wishes, wants, and desires. After a friend of Jack’s, Arthur wraps up his performance of Ethelbert Nevin’s The Rosary, Jack confidently gets up on the stage and assumes a playing position on the piano.

Before long, an audience member starts heckling the newcomer: “Can he really play?” Arthur responds: “Heavens no! He never played a note in all his life…” The opening section slowly turns up the anxiety in the room, mimicking how people typically stress out over major upcoming events and thus triggering their insecurities. It speaks directly to the audience by invoking the emotion of shame.

According to Eugene Schwartz, an effective copy should elicit strong emotions in your readers such as fear, shame, or desire. Emotionally charged readers are more likely to read your advertisement until the end, increasing your chances of converting them to paying customers.

Then, Jack starts playing the piano and everyone who laughed at his antics suddenly falls silent, like in a trance: “Instantly, a tense silence fell on the guests. The laughter died on their lips as if by magic. I played through the first bars of Liszt’s immortal Liebestraume. I heard gasps of amazement. My friends sat breathless—spellbound.”

Pulling off a twist for the ages, John Caples transforms the pent-up anxiety into a desirable outcome for everyone at the party. Jack gets to enjoy his playing experience in front of a live crowd, while the audience gets to hear an emerging talent demonstrating his piano skills for the first time.

Finally, after the excitement dies down, Jack reveals his secret: “Have you ever heard of the U.S. School of Music? They have a new simplified method that can teach you to play any instrument by mail in just a few months.”

John Caple’s ad through the lenses of Joseph Campbell’s The Hero’s Journey

Knowingly or not, Mr. Caples borrows elements from the cyclical nature of the hero’s journey to take the ad’s readers on a wild ride. It’s a notable instance where direct response copywriting brushes shoulders with select mythology tropes to augment an otherwise mundane mail-order advert into something truly special.

The playing stage delineates the barrier between the known and the unknown world. Jack, feeling the call for adventure, braves his fears and passes the threshold without flinching an eye. The piano assumes the role of the monster, which Jack needs to tame to overcome his anxiety.

At this point, Jack’s already gone through the wringer, tamed the monster by learning how to play the instrument, and conquered his inner fears months in advance. However, the audience doesn’t know that and expects Jack to bomb or perform some kind of practical joke.

To their surprise, Jack goes through the proverbial death and rebirth in a single sitting, with the U.S. School of Music acting as his mentor throughout the entire journey. After the reveal, John Caples organically introduces the unique sales proposition (USP) to the story: “It seems just a short while ago that I saw an interesting ad of the U.S. School of Music mentioning a new method of learning to play which only cost a few cents a day!”

Not only that, but this new system allows students to master playing an instrument without the presence of a teacher: “The ad told how a woman had mastered the piano in her spare time at home—and without a teacher!”

Lastly, Jack reveals his key helper: “When the course arrived I found it was just as the ad said— as easy as A.B.C. And, as the lessons continued they got easier and easier. Before I knew it I was playing all the pieces I liked best. Nothing stopped me. I could play ballads or classical numbers or jazz, all with equal ease! And I never did have any special talent for music!”

Thus, John Caples ends the hero’s journey and closes the story’s cycle, generating a desire in the readers to become as good at playing the piano as our lovable protagonist Jack. Additionally, creating desire is the third stage of the AIDA copywriting framework.

Ending the advert on a strong note

The second to last section of the ad titled “Play Any Instrument” talks directly to the target audience, persuading readers that they too can replicate Jack’s success quicker than if they took traditional lessons: “You too, can now teach yourself to be an accomplished musician—right at home—in half the usual time.”

Finally, the ad ends with an enticing CTA, which also doubles as the fourth and final stage of the AIDA copywriting framework: “Right now we are making a Special Offer for a limited number of students. Sign and send the convenient coupon now—before it’s too late to gain the special benefits of this offer.”

What a great ad. It keeps readers engaged, it never gets dull, and it ends with a clear CTA that urges prospects to act immediately or lose out on the limited-time offer.

As a final note, keep in mind that this advert performed very well for its time. Today’s contemporary audience, however, is all but desensitized to this mythological storytelling approach and long-form type of copywriting.

Unless you’re a god-tier copywriter, don’t just copy and paste John Caples’ writing style down to a tee. Instead, try to adapt his ad structure to serve your specific needs, modernize the style to resonate with your target market, and be honest with your audience about your products and services. Following these core copywriting tenets will help you improve your campaigns’ conversion rate optimization (CRO), leading to a significant uptick in sales over the long haul.

Other Classic Examples of Direct Response Copywriting

In addition to John Caples’ masterpiece, there are other direct response copywriting examples that are also worth mentioning. Here are some of the most prominent ones from the classical era of print marketing.

David Ogilvy’s The Man from Schweppes ad

In this ad, Mr. Ogilvy used a real executive from Schweppes to pique curiosity and generate interest in new readers. The copy is relatively short, but it’s filled with keywords such as “authentic”, “unique”, and “perfection”, giving off a sense of high class, luxury, and exclusivity.

It’s a good example of conveying the most information to buyers without going overboard with the length of the copy.

Joe Sugarman’s BluBlocker ad

Joe Sugarman helped BluBlocker sell at least 20 million pairs of their flagship sunglasses thanks to this ad. The ad has everything, including an intriguing headline (“Vision Breakthrough”), an eyebrow-raising Caples-inspired tagline (“When I put on the pair of glasses, what I saw I could not believe. Now will you.”), and a captivating copy structure that frames the sunglasses in the most positive light imaginable to humankind.

Simply stated, it ticks all the boxes it needs to sell a quality product without exaggerating its benefits or downplaying its cons.

Eugene Schwartz’s Food is Your Best Medicine ad

Whether or not you agree with the titular book’s key premise, the ad itself is a winner on all fronts.

First, it uses an emotionally charged headline to get your attention: “Food is Your Best Medicine.” Then, it stirs up controversy to keep you interested: “This is possibly the most controversial medical book for the public ever written.” Finally, it tells a sprawling story of a notable physician who practiced a holistic approach to everyday living in order to inject a newfound vitality into his life.

Bill Bernbach’s Think Small ad

Bill’s visually striking Volkswagen advertisement aims (and succeeds) to turn the existing conventions of that time on its head. It challenges the prevailing notion that bigger is always better by offering an alternative solution to an overly saturated car market—the Volkswagen Beetle.

After capturing the audience’s attention with an intriguing headline (“Think small”), the copy then goes on to explain the Beetle’s key strengths in a clear, simple, and concise way.

Victor Schwab’s How to Win Friends and Influence People ad

Arguably, Dale Carnegie’s self-help book “How to Win Friends and Influence People” was destined to become a success no matter what—with or without direct response advertising. But, Mr. Schwab’s marketing campaign definitely made a positive impact on the future trajectory of the book’s sales.

In it, Victor Schwab leveraged the power of genuine testimonials from people whose lives were improved by applying Mr Carnegie’s strategies in their daily routines. These segments emphasized lasting improvements in both interpersonal relationships and professional environments thanks to revamped communication skills on the part of Mr. Carnegie’s pupils.

5 Core Principles of Direct Response Copywriting from Master Copywriters

The fathers of long-form advertising copy had decades of experience to perfect their craft and test various theories in the real world. Some of these theories became the cornerstone of modern direct response copywriting, and here are five of them to prove that notion.

Creativity is useless unless it sells (David Ogilvy)

David Ogilvy, touted by many as a true advertising wizard, was once caught saying: “In the modern world of business, it is useless to be a creative, original thinker unless you can also sell what you create.”

Ogilvy is 100% right. If your creativity eclipses the usefulness of your copy, you’ll have a hard time selling your product or service to customers who need it the most. Cute copy that’s also rich in purple prose, figures of speech, and various creative somersaults of the written word, is practically worthless unless it can convince your target audience to convert.

A great headline is the most important part of your marketing campaign (Gary Halbert)

Getting someone’s attention is very difficult. It requires them to leave whatever they were doing before reading your headline and shift their attention to your copy. This is where a great headline can pull through in your favor.

In one of his letters to his son, Gary Halbert emphasized the importance of writing compelling headlines. Specifically, he understood that specific headlines are better at grabbing your attention than generic headlines. If people can’t be bothered to read your headline, how are they going to find out about your brand?

Here’s an example of a generic headline and its specific counterpart:

- Generic—”How To Become a Better Direct Response Copywriter”

- Specific—”Three Steps To Increase Your Online Ad Conversions by 25% Without Spending a Fortune”

The first headline is too generic to be interesting. The second headline is more descriptive, offering a realistic benefit (“increase your online ad conversions by 25%”) and an intriguing hook (“without spending a fortune”) to capture incoming leads. Which headline is likely to generate more clicks?

Whether you’re using AIDA, PAS, or a different formula to create your headlines, make sure they’re as intriguing, descriptive, and specific as they can be.

Failure is a natural part of growth (Eugene Schwartz)

A great copy is built on top of a mediocre copy. And mediocre copy fails more often than it succeeds in the marketplace of ideas. So, to assemble a great copy, first, you must test different copy elements until some of them fall into place and produce a lasting winner.

In Breakthrough Advertising, Eugene Schwartz illustrates the concept of failure as a normal part of becoming a great direct response copywriter: “A very good copywriter is going to fail. If the guy doesn’t fail, he’s no good. He’s got to fail. It hurts. But it’s the only way to get the home run the next time.”

A concrete reason to buy is more powerful than a flashy ad (Claude Hopkins)

Claude Hopkins, another copywriting legend, was a firm believer in the power of reason-why advertising. This marketing philosophy relies on a scientific approach to advertising more than it values flashy images, loud sounds, or clever product mottos. In other words, copywriters should always strive to give a concrete reason why a product or service is worth buying and avoid fluff in their campaigns.

Following Mr. Hopkins’s reasoning, advertising had to be treated as hard science instead of a guessing game. As such, he performed regular testing to weed out the losing elements in search of his best-performing copy.

So, if you have your hands on more than a single promising headline, it’s a good idea to start testing your headlines and let real people filter out the losers from the home runs over a reasonable timeframe (3-4 weeks of extensive A/B testing should do the trick).

Reading your copy should be equivalent to coming down a slippery slide (Joe Sugarman)

Once prospects get past the initial headline, it’s the copywriter’s job to keep them engaged until the end of the copy. There, you can reinforce your USP and introduce an irresistible CTA to close out the deal.

Joe Sugarman compared this process to sliding down a slippery slide, where your prospect is moving through the copy at a rapid pace until they’re ready to spring into action and take you up on your offer at the finish line.

The best way to apply this technique is by giving the prospect a reason to care, typically by grabbing their attention (AIDA) or by uncovering a seemingly unsolvable problem (PAS) in the first few sentences of your copy. Professionals often argue about the effectiveness of the AIDA formula over the PAS copywriting framework, to which we say: both formulas have their use cases and are proven to work well under different circumstances.

Anyway, once you have your prospect hooked, it’s time to guide them through the copy in a way that feels natural, educational, and relevant. Your language should be clear but not boring, nudging your prospects to keep reading without doubting the validity of your campaign.

They simply can’t resist until they’re done—just like coming down a slippery slide.

How Direct Response Copywriting Differs from Normal Copywriting

While there’s certainly some overlap between normal and direct response copywriting, they’re not the same. Unlike conventional copywriters, their direct response counterparts are tasked with running the entire sales process—starting from the initial prospect awareness and going all the way to closing a sale.

Direct response copywriting moves prospects through all five stages of the marketing funnel, including:

- Awareness

- Consideration

- Conversion

- Loyalty

- Advocacy

A direct response copy contains a clear CTA, while a normal copy typically does not. Also, a direct response advertising campaign is measurable, which means you can count the response rate, CRO, and return on investment (ROI) on both your ads and organic placements.

On the other hand, assembling a normal (for example, brand-oriented) copy is just one step of the overall buying process. This type of copy doesn’t motivate readers to take immediate action. Instead, it’s composed in a way to remind your prospects about a certain product or service whenever they encounter it in the wild—either outside on a supermarket shelf or online on a site.

A great example of a perennial brand-oriented copy comes in the form of Coca-Cola’s recurring Christmas video ads. The ads have high production values, they’re great to look at, and they illicit strong positive emotions among buyers, but they also have a fairly simple script and they don’t show a CTA anywhere on the screen throughout their runtime (although, their latest Christmas ad was found to be AI-generated, which the online audience didn’t appreciate as much—to put it lightly).

Remember: The Coca-Cola Company’s goal is to remind or introduce its target market to its flagship soda without generating an immediate response from customers. So, in a way, you can’t place with 100% certainty a definitive causation between the fluctuation of Coca-Cola soda bottle sales at the time of airing these ads, even if a positive correlation is plausible.

When to Use Direct Response Copywriting

Use direct response copywriting when you need to:

- Write a persuasive copy to make the sale immediately as opposed to an unspecified time in the future

- Write long-form copy (some exceptions apply)

- Speak directly to your target audience

- Convert warm leads into paying customers

- Write copy for all five stages of the sales funnel

- Write online copy such as email newsletters, social media ads, one-page sites, banner ads, and landing pages

- Write offline copy such as TV infomercials, radio ads, magazine space ads, direct-mail letters, and point-of-sale displays

Lastly, the heart and soul of direct response copywriting is perhaps best reflected through this Ogilvy quote: “Do not address your readers as though they were gathered together in a stadium. When people read your copy, they are alone. Pretend you are writing to each of them a letter on behalf of your client.”